The (old) New Churchyard -a way tl;dr excerpt on those Crossrail Skellies

Mostly,

I thought I ought to put this up as a tribute to the late Bill White, who was a

font of knowledge on all manner of Londoners long since gone to ground. What

I’ve recorded here as ‘pers. Comm’ can now be found in the published monograph

(cite), but I like to remember it coming straight from Bill himself; his funny,

fascinating I insights that I would slowly absorb along with the heat from the mobile radiator set against the arctic cold of the infamous Rotunda.

Excerpt below from my phd (Hassett, B. R. 2011. Changing World, Changing Lives: Child Health and Enamel Hypoplasia in Post Medieval London. London: University College London).

The New Churchyard at Broadgate (LSS85)

The New Churchyard was established in 1569 as an

extramural interment ground for the ‘overflow’ of deceased from city parishes

though it increasingly became associated with the Bethlehem Hospital nearby and

came to be known as Bethlehem burial ground on later maps (Harding,

1998; Harding, 2000). The

last burial in the New Churchyard was recorded in 1714 (B. White; pers. comm.);

inhumations in this assemblage are the earliest group studied. The cemetery was

varied in socioeconomic composition, accommodating not only those who could not

afford the sometimes exorbitant burial costs in their own parish, but also

burials for which their simply was no room in times of catastrophic mortality

(i.e. plague years). It also functioned to absorb all of the London dead who

did not belong in the traditional place of burial, the home parish, for reasons

of penury, anonymity, moral failure, or religious dissent (Harding,

1998; 2000).

The burial assemblage studied here was recovered during

the Broad Street excavations carried out by the Museum of London Archaeological

Service (MoLA) from 1984 from an area near Liverpool Street Station in east-central

London. This assemblage is possibly the least economically or geographically

coherent used in this project. There is a strong suggestion in historical

accounts that the dead in the New Churchyard largely represent a particular

class of Londoner, aliens and those of low socioeconomic standing rather than a

mixed group organised on more traditional, geographically-bounded parish lines.

The location of the cemetery itself reflects its role in

housing the marginal after death. It was set up outside the City walls in what

would become the suburban parish of St. Botolph Bishopsgate, but was in the

mid-1500s a landscape of fields and open spaces. The land was adjacent to the

small church of Bethlehem and the land for burial a gift of the Mayor Sir

Thomas Roe (or Rowe) in 1569, who subsequently buried his wife in the new

ground (Stow,

1598). Further building in the

area would see the construction of the infamous Bethlehem Hospital, or Bedlam,

nearby (Harben,

1918), and there is

considerable interest on the part of Victorian chroniclers of the London dead

in the prospect that the burials represent the inmates (Holmes,

1896). Residential building on

what remained of the ground seems to have been carried out in the 17th

and 18th centuries until eventually Broad Street Station, later

Liverpool Street station, was established in 1875 (Harben,

1918). The development of

Broad Street appears to have revealed considerable amounts of human remains;

many of these are attested as uncoffined, and ‘collected into heaps’ (Macdonell,

1906p. 87) . It

seems possible that these ‘heaped’ remains originate at least in part in the

mass burial pits London is said to have resorted to during times of epidemic

mortality, particularly during plague years, Stow reports a plague burial

ground near Old Bethlehem in Moorfields (Harding,

1993; Macdonell, 1906; Stow, 1598). The alternate possibility that they represent simply disturbed

remains hastily reburied during earlier construction is dismissed by reference

to later sequences of street foundations by an early researcher into the

morphology of the English skull, who reports on cranial measurements taken from

a large group of skulls uncovered during excavation of a latrine in 1903 and

previous excavation in advance of the foundation of Broad Street Station in

1863 (Macdonell,

1906); these were apparently

curated at University College London though no trace remains of them. The

number of individuals in the assemblage used here who may have been interred in

some form of mass burial pit is unfortunately unclear, but there is the

suggestion that the earliest burials excavated by MoLA were from mass burial

pits and many of the later burials were inhumed in oak coffins (B. White, pers.

comm.).

This extra-mural location was apparently not viewed very

favourably by Londoners; burial in the New Churchyard was appreciably cheaper

than in many parish churches. Harding (2002,

p. 97) cites a Katherine Chidley

in 1641 who describes burial in ‘Bedlam’ as the ‘cheapest she knows’. Several parishes record burials of

their number in this New Churchyard, among them All Hallows Honey Lane (Keene

and Harding, 1987), but

it may have been particularly used by the local parish, St. Botolph Bishopsgate

(Holmes,

1896). Poverty was not the

only impetus for Londoners to seek (or accept) burial there, however. A large

number of inhumations in the New Churchyard may derive from times of epidemic

mortality, as mentioned above, and may have come from many different locations

in the City or in the suburbs.

There were other reasons to actively choose to be buried

in the ground as well; chief among these was the sort of identity politics of religion

which was such a salient feature of the late medieval and post-medieval city.

One of the clearest examples of this can be seen with the popularity of the New

Churchyard as a burial ground amongst the gathered churches of the late 16th

century. Robert Lockyer, a rabble-rousing proselytiser for the Leveller

movement, was very publically mourned as he was interred in the New Churchyard;

both his interment in the cemetery and long public funeral procession were

highly politicized, public acts (Gentles,

2004). Other members of the

Gathered churches and foreign Christians also specified their desire to be

buried in the non-denominational ground (Harding,

2002). The Dissenting

religionists interred in the New Churchyard were not by necessity poor; many of

them were comfortable burghers such as Ludowicke Muggleton and John Reeve,

founders of the short-lived (and very small) 17th century Protestant

sect of Muggletonians (Lamont,

2008).

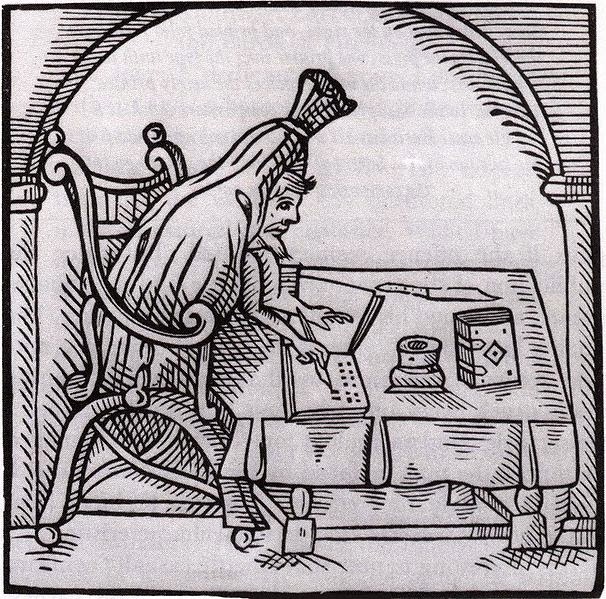

One Robert Greene (1558-1592)

provides a lively example of another of the paths leading to the New Churchyard

(Harding,

2002). Originating in Norwich,

he may at some point have entertained notions of becoming a physician, and

obtained degrees from both Cambridge and Oxford (Newcomb,

2004). He may have subsequently

married, impregnated, and abandoned a wife in Norwich, after divesting her of

much of her fortune; in London, he became a well known libertine, actively

cultivating his own legend as witty, irreverent figure in a series of

pamphlets. He wrote plays with the group known as the University Wits, which

also included notables such as Christopher Marlowe, and left behind a

considerable literary output. Nonetheless, he ended his days dissolute and

destitute, dead of ‘eating too much pickled herring and drinking too much Rhenish

wine’ according to contemporaries (Kinney

and Lawrence, 1990, p 157). He

was buried in the New Churchyard 1592, and an image of him in scribing away in

his funeral shroud was published by fellow writer John Dickenson in 1598, somewhat

ignominiously commemorating the character suggested as the basis for

Shakespeare’s Falstaff (Dickenson,

1598).

|

| Robert Greene shown writing, in his shroud. Plate from Dickenson, 1598. |

|

| Robert Greene devoted some of his limited time on earth to slagging off other writers: he did not think much of this Shakespeare guy. |

*yes I stole that from Douglas Adams.

Dickenson J. 1598. Greene in conceipt new raised from

his grave to write the tragique historie of faire Valeria of London; . wherein

is truly discovered the rare and lamentable issue of a husbands dotage, a wives

leudnesse, and childrens disobedience. received and reported by J. D. London:

Richard Bradocke for William Jones.

Gentles IJ. 2004. Lockyer, Robert

(1625/6–1649). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford

University Press. p http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/47102.

Harben HA. 1918. Berwick Alley -

Billingsgate Market. A Dictionary of London: Centre for Metropolitan History. p

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/.

Harding V. 1993. Burial of the plague dead

in early modern London. In: Champion JAI, editor. Epidemic Disease in London.

London: Centre for Metropolitan History p 53-64

---. 1998. Burial on the margin: distance

and discrimination in early modern London. In: Cox M, editor. Grave Concerns:

death and burial in England 1700-1850. CBA Research Report 113. York: Council

for British Archaeology

---. 2000. Death in the city: mortuary

archaeology to 1800. In: Haynes I, Sheldon H, and Hannigan L, editors. London

Under Ground: The Archaeology of a City. Oxford: Oxbow Books. p 272-283.

---. 2002. The Dead and the Living in Paris

and London, 1500-1670. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holmes I. 1896. The London Burial Grounds:

Notes on their history from the earliest times to the present day. London: The

Gresham Press

Keene D, Harding V. 1987. All Hallows Honey

Lane. Historical gazetteer of London before the Great Fire: Cheapside; parishes

of All Hallows Honey Lane, St Martin Pomary, St Mary le Bow, St Mary Colechurch

and St Pancras Soper Lane. p 3-9;

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=8466.

Kinney AF, Lawrence J. 1990. Rogues,

Vagabonds, & Sturdy Beggars: A New Gallery of Tudor and Early Stuart Rogue

Literature Exposing the Lives, Times, and Cozening Tricks of the Elizabethan

Underworld. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Lamont W. 2008. Muggleton, Lodowicke

(1609–1698). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University

Press. p [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/19496, accessed 19427 March 12010].

Macdonell WR. 1906. A Second Study of the

English Skull, with Special Reference to Moorfields Crania. Biometrika

5(1/2):86-104.

Newcomb LH. 2004. Greene, Robert (bap.

1558, d. 1592). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford

University Press. p [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/11418, accessed

11427 March 12010].

Stow J. 1598. The Survey of London.

Kingsford CL, ed.

ReplyDeleteExcavation is not a random thing to do. There are methods employed to do the excavation properly and safely. Read what they are before doing any excavation work.Excavation Company Massachusetts